Culture plays a major part in the success of your design system

Author

Nico ten Hoor

Published

17 January 2023

Reading time

6 minutes

Ben Callahan argues that the best way to approach creating a sustainable, systematic design practice is to understand and recognize the impact of culture within the organization. I agree and have seen the lack of focus on culture impact the outcome.

Recently I participated in Clarity 2022, one of the most renowned design systems conferences. One talk stood out to me in particular; what follows is my recap of the talk ‘Design Systems Culture’ by Ben Callahan. Ben Callahan is the president of Sparkbox, an agency in web design and development. Or in their own words: Sparkbox partners with complex organizations to create user-driven web experiences.

Organizational culture

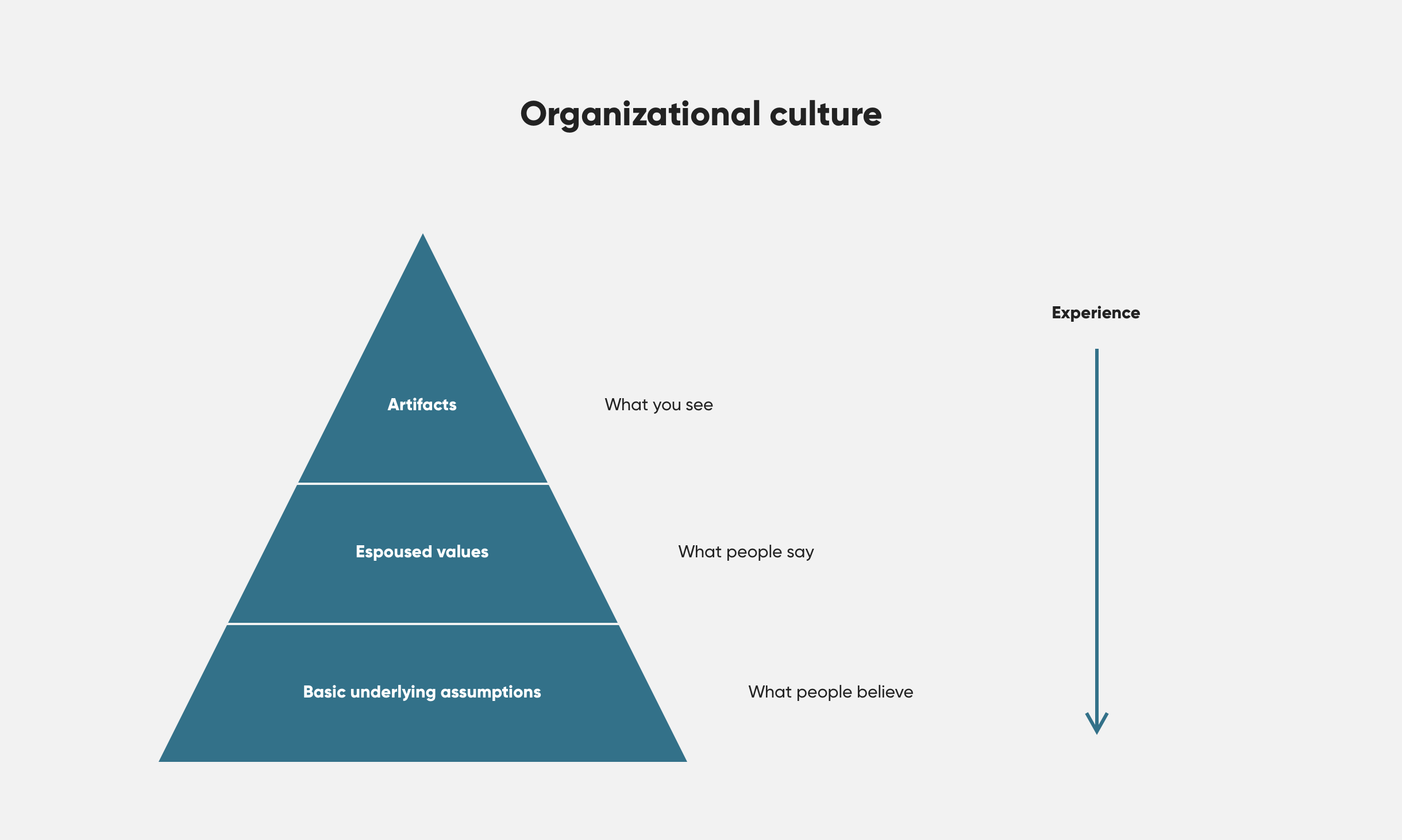

His talk started by mentioning some sentiments regarding design systems teams operating in complex organizations, such as: ‘Design system leaders don't have experience with collaboration because they operate like an ivory tower.’ Clearly, we can already see the tension between the embedded design systems team and the host organization; forces of culture at play. But what is culture anyway? Here Ben used the three layers of organizational culture by Edgar Schein of the Sloan School of Management wherein an organization’s culture gets divided into three distinct levels: artifacts, values, and assumptions.

- Artifacts are the overt and obvious elements of an organization. Artifacts are easy to observe but difficult to understand.

- Espoused values are the company’s declared set of values. Values affect how members interact and represent the organization.

- Basic underlying assumptions form the basis of the organizational culture. They are beliefs and behaviors so deeply entrenched that they sometimes go unnoticed, but basic assumptions are the essence of culture.

The organizational culture model goes a long way in explaining people's value drivers, what motivates them and why they behave in a certain way. Knowing the factors (i.e..: their values and beliefs) that define a culture, we can find common ground when working with people if we know what their fears are and what drives them.

Dimensions of culture

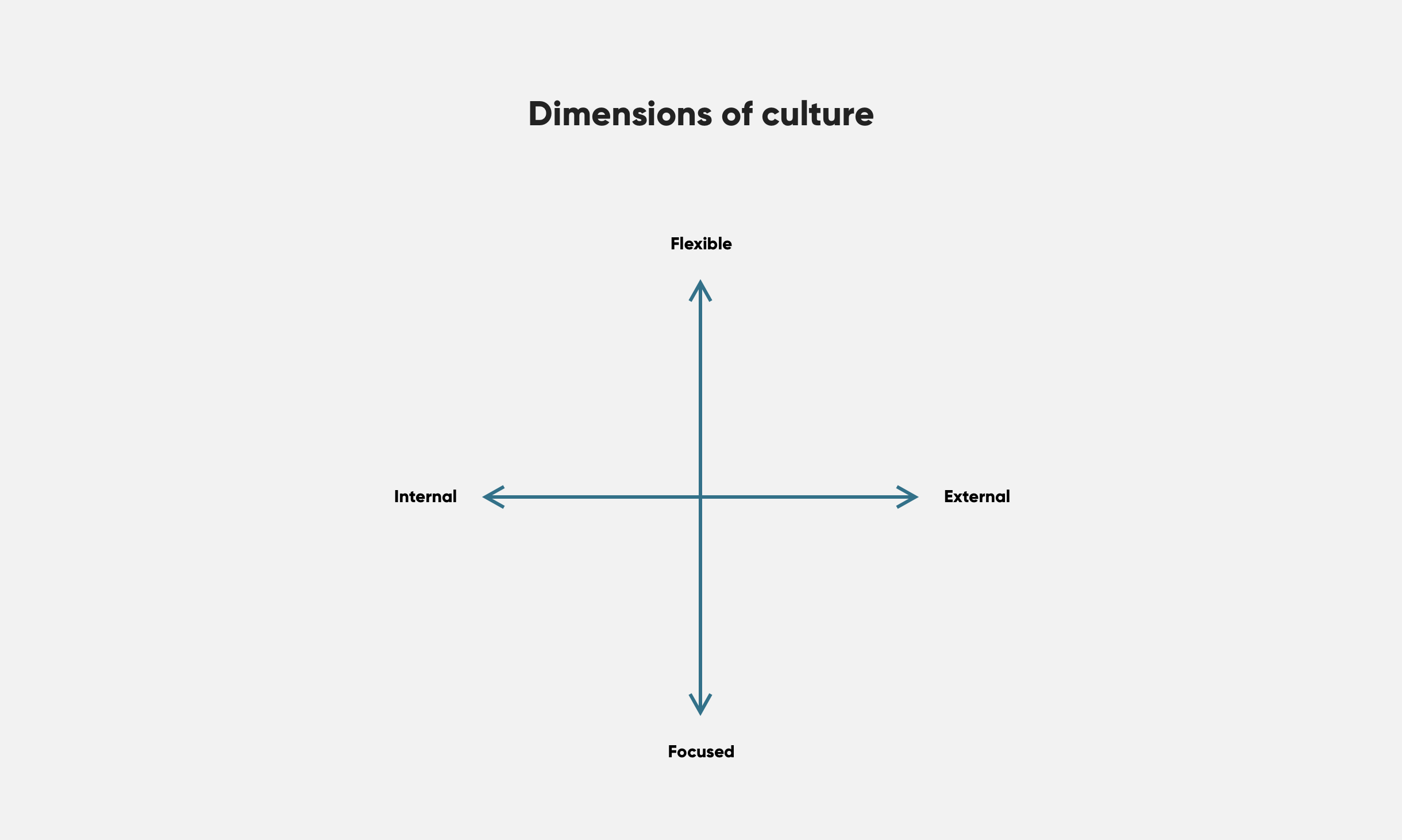

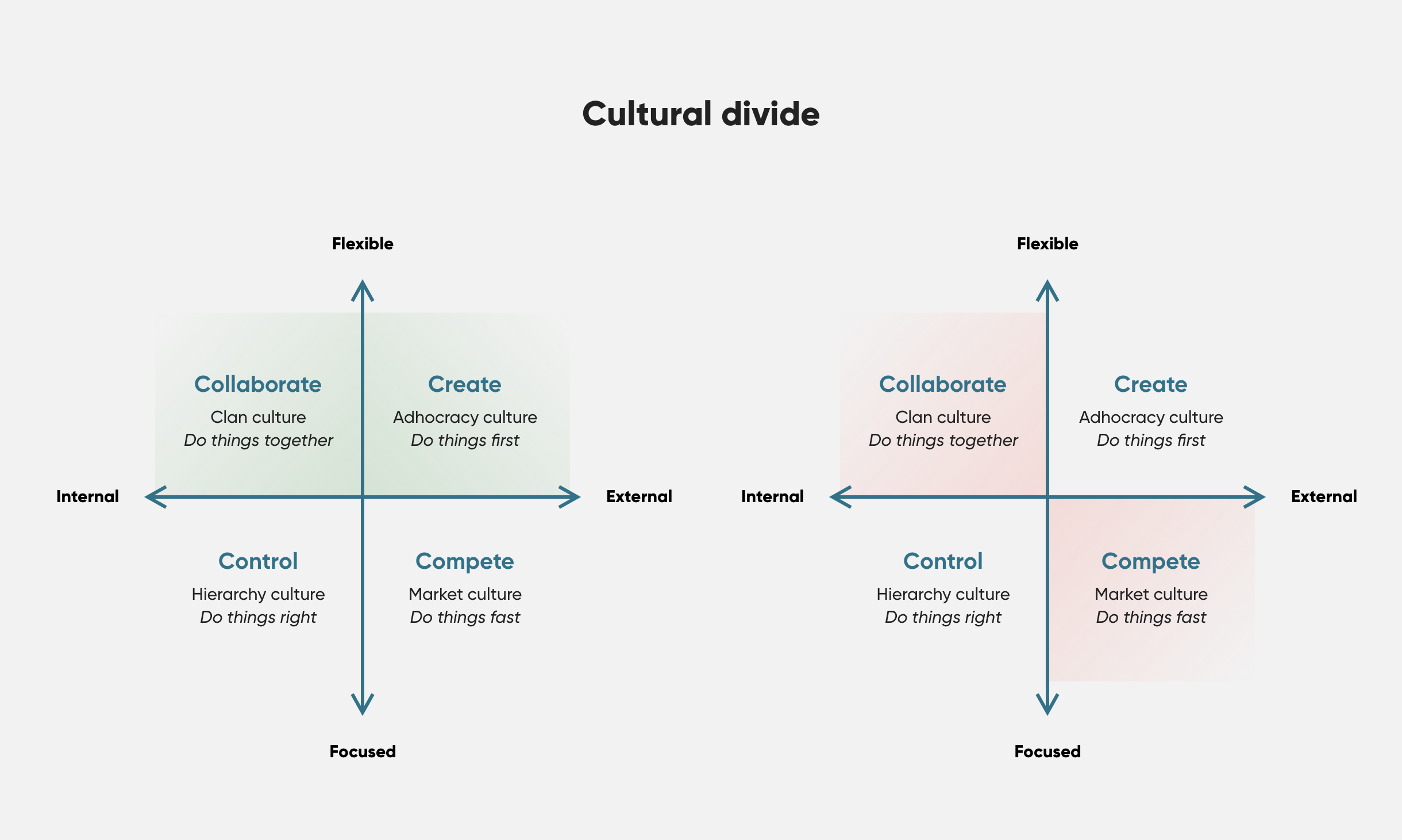

As cultures may differ in numerous ways is there a way to grasp the overall tendencies? Ben introduced the Competing Values Framework as a way to categorize primary types of culture. Initially developed from research conducted by the University of Michigan and followed by studies of organizational culture, leadership roles, management skills, and information processing styles, two major dimensions consistently emerged.

One dimension differentiates between a flexible and a focussed culture, the second differentiates between an emphasis on the internal versus the external.

Ben then explains that the culture of the design system is by definition internal, while the rest of the company has more of an external mindset. Now there are different ways to act recognizing the internal versus the external and trying to bridge the polarities. For example, in 'Team Models for Scaling a Design System' Nathan Curtis discusses different ways of governing a design system varying from centralized (very much internal) to federated (decided by external teams). Yet, by nature design systems remain an internal matter.

It would appear to me little is published about the other axis. Here Ben surprised me with insights that help explain deep-rooted motivations and understand what kind of behavior is rewarded in certain cultures.

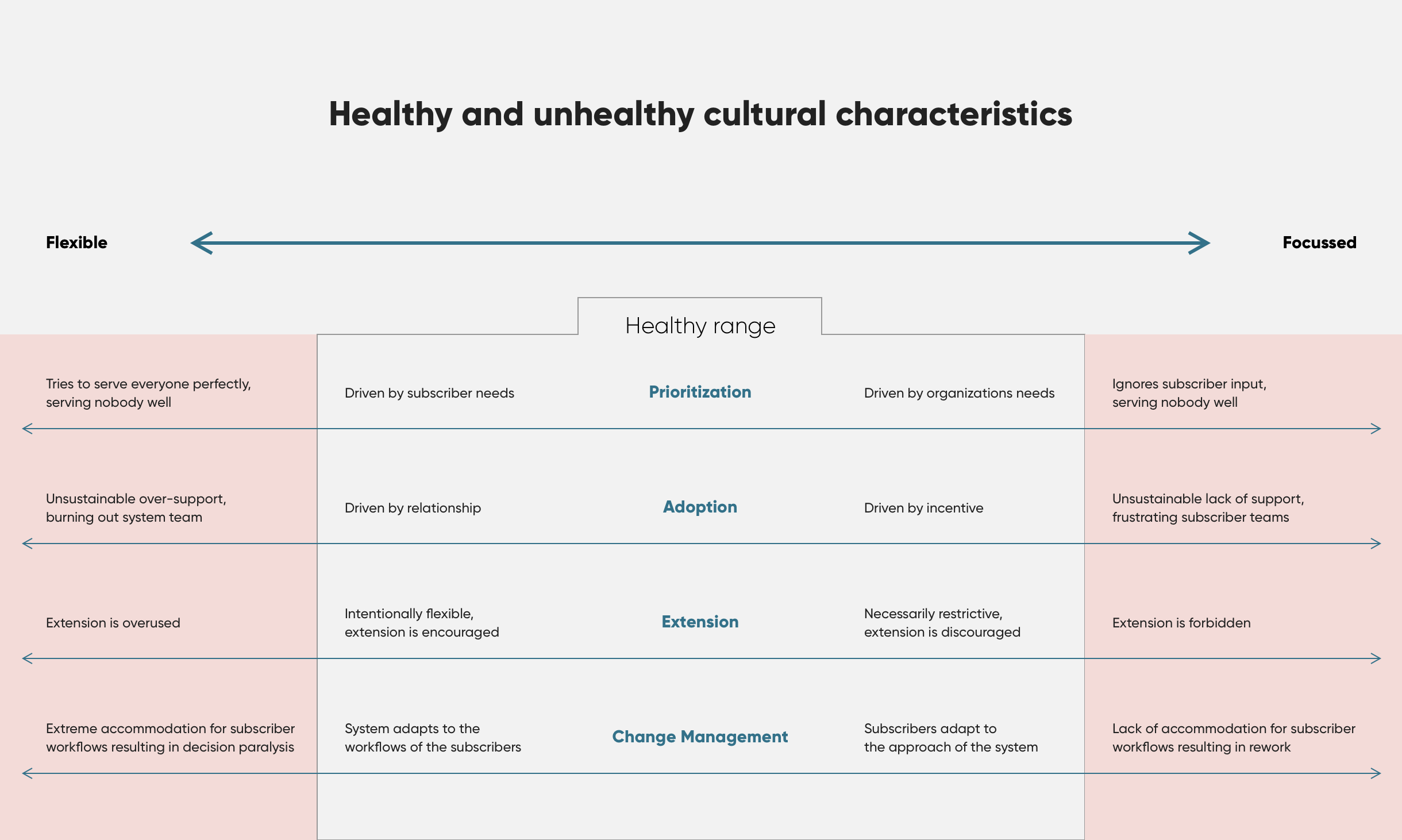

A flexible versus a focused culture

It is important to understand that the properties Flexible and Focussed are not in themselves good or bad. Based on their basic underlying assumptions Design system teams tend to value one over the other while probably being unaware of doing so. This can lead to healthy as well as unhealthy behaviors.

For example, a design systems team that values flexibility and collaboration will prioritize based on subscriber needs, meaning the ones who use the design system. Alternatively, a design systems team that is focused and values rigor will prioritize based on the needs of the organization. Both positions are defensible and not inherently wrong in themselves.

Prioritizing too much on subscriber needs, meaning trying to prioritize everyone will serve nobody well. On the other hand, prioritizing the needs of the organization too much, ignoring the subscriber's priorities, again leads to serving no one well.

The same argument can be made for topics other than prioritization: consider your motivations, be mindful of your drives.

According to Ben, the unhealthy characteristics are a result of culture driven too much to either side of the spectrum. Thus, his advice to design systems teams is staying within a moderate range of the spectrum.

Competing values framework

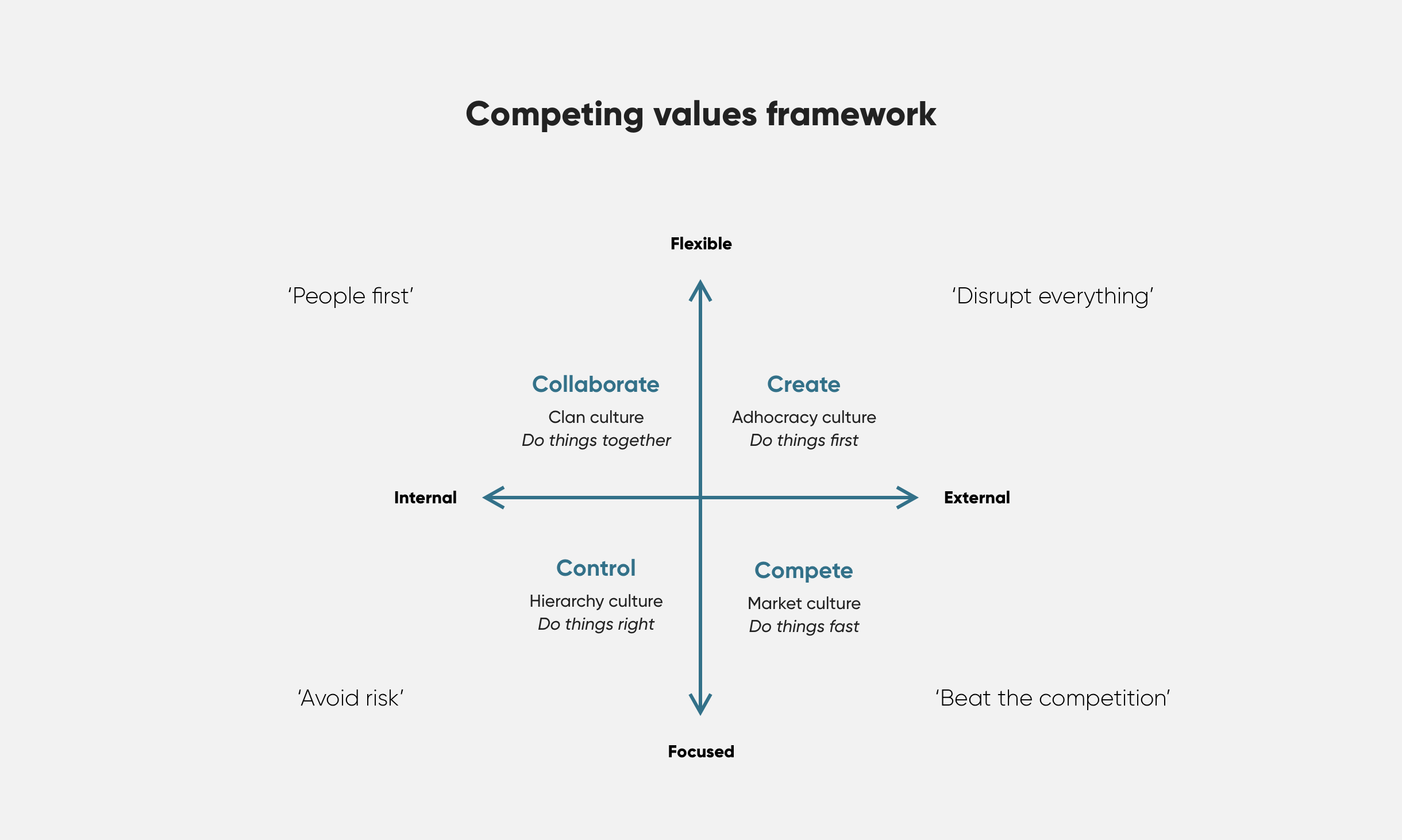

The next step is to fill the matrix with four sections. Let's look at them, starting from the top left quadrant and going counterclockwise, the first two are the cultures that design systems teams usually fall into:

- Collaborate emphasizes an internal focus and values flexibility and harmony. Also known as Clan culture characterized by wanting to do things together.

- Control also emphasizes an internal focus but is more of a strict and focused nature. Also known as Hierarchy culture characterized by wanting to do things right.

- Compete shares the strict and focused nature of Control, but emphasizes an external focus. Also known as Market culture characterized by wanting to do things fast. Larger companies typically fall into this quadrant.

- Create also emphasizes an external focus but values flexibility. Also known as Adhocracy culture characterized by wanting to do things first. Startups or companies with a drive for innovation usually fall into this quadrant.

So much for the theory; all nice and swell. But what does this teach us about advancing design systems?

Collaborate quadrant

Let's say the design system started from the design department, but getting developers on board is proving difficult. Working towards shared values could be a way to ease this. For example, if you notice a passion for open source communities among developers, capitalize on this by setting a goal to open source the design system. Valuing harmony we are now cultivating Clan culture, we are in the Collaborate quadrant.

This could work very well for the design systems team in this example, but ultimately the goal is to bring a shared design systems vision across the company. As our team works hard to improve the design system, Ben argues that the design system can be a catalyst, but it won't do it alone. As mentioned, the rest of the stakeholders are probably externally focussed.

If we are in a Startup or a company with a penchant for innovation (the Create quadrant), the flexible approach of the Collaborate quadrant should go a long way in bridging the gap. If we are in a larger company, however, a company cultivating Market culture (the Compete quadrant) we see that the cultures are now diagonally opposed. This, according to Ben, is like trying to mix oil and water. Not so great. In this situation enforcing stricter rules and achieving more clarity would be a sound move in climbing the cultural divide.

Control quadrant

Alternatively, you could find yourself in the Control quadrant while the rest of the organization is in the Create quadrant; again diagonally opposed. Now opening up to flexibility would be the logical thing to do. As an example, think about allowing the context to play a bigger part in legitimizing variations of components. Teams that tend to experiment are now more capable to create the user experience they aim for. A good way to escape the ‘ivory tower syndrome’ mentioned in the start of this post.

Conclusion

What I took away from the talk is that in order to advance the design system within the organization, design system teams need to take into account the primary culture they operate in as well as being aware of their own subculture. We, at Informaat, have had success in mapping cultural values with our True Experience approach and Ben’s thinking fits and expands on that.

The two lessons learned:

- Being aware of one's own cultural orientation and being considerate not to stray too far to the extremes of the spectrum.

- When your design systems team is diagonal to the culture of the rest of the organization, try steering in the opposite direction of the vertical axis.

About the author

Design system

True experience